INTRODUCTION

Brief Overview of Economics and Introduction to the Short Course

Economics is a broad area of study that encompasses the following areas of learning and concepts:

- business management

- finance

- foreign and domestic market activities, which include the production, management, sale and distribution of goods

- government policies

- bank policies

- money market, foreign currency valuation, and exchange, and

- the sociological and behavioral impact on nations, industries, companies, sectors, households, and individuals when various economic phenomena prevail at a specific time, such as:

- a scarcity or surplus in commodities

- a financial crisis, such as a recession, or worse, an economic depression

- market equilibrium

All these fields are interrelated and define what economics is, and guide economists and policymakers In the bigger scheme of things:

- the commodities to produce or trade

- how or when to trade the commodities

- when to devalue a product or a currency

- when to liquidate fund reserves to prevent the economy from plunging.

In a more localized view, economics help households make efficient appropriations of their monthly budget. It also guides them whether to buy a property or not, whether to purchase a health insurance or not, or in some cases, if moving to a state with more reasonable interest rates and median salary has a much better outlook.

Simply put, economics is all about sound decision-making, and what drives humans to make these decisions, on either a macro or micro scale, is the scarcity of resources.

This crash course will focus on macroeconomics or the bigger economic picture. By adopting a bootcamp approach catered for novice readers, it will present the fundamental macroeconomic theories and concepts that gave birth to the sub-field and helped define it through time.

It will integrate the concepts with real-life applications, such as the different macroeconomic policies governments have in place, using the U.S. as an example. It will also mention other relevant phenomena such as the 2008 recession and the impending (as of writing) 2020 coronavirus recession. Each topic ends with a list of the key takeaways and points or questions self-reflection.

What is Macroeconomics?

Macroeconomics is the stuff that finance news and reports on TV, radio, or in print are usually made of. When news outlets like CNN Money, CNBC, MSNBC, Bloomberg, or Wall Street Journal talk about a nation’s GDP, inflation, employment rate, interest rates, exchange rates, or the stock market, they are all speaking the macroeconomic language. Macroeconomics examines the economy from a larger lens – could be from a global perspective or a national perspective.

Macroeconomics examines the economic interdependencies of nations and industries. It takes into account the driving forces or aggregated indicators such as the GDP, inflation, unemployment rate, and interest rates.

These indicators help shape the economic policies instituted by governments or financial institutions like banks, and strongly influence any of the economic phenomena enumerated below that prevail at a particular time.

Examples of these phenomena are:

- Economic growth, like the economic expansion of the U.S., hailed the longest ever from 2009 to January 2020 (Forbes.com, 2020), or that of China, whose five-decade transformation from an agrarian economy to a global superpower has made the country the poster child for globalization and open trade policies (World Economic Forum, 2015)

- Market equilibrium, as what has been observed in the U.S. oil and petroleum market in 2016 (Marketwatch.com, 2016), or,

- Economic recession, like that in 2008, where the global economy spiraled so bad, former Federal Reserve head Ben Bernanke almost compared it to the Great Depression of 1929 (CNN Money, 2014). In fact, for 2020, with the entire world grappling with the physical, psychological, and economic effects of the coronavirus, economists ponder if the macroeconomy is headed for the worst (Huffington Post, 2020).

Why Study Macroeconomics?

A 2009 paper published by the University of West England – Bristol, which interviewed economics students via an online questionnaire and focus group discussions suggested that students perceive the course as their tool to understand global issues. That understanding also arms them with competent decision-making skills (remember the introductory part about sound decision-making skills thanks to econ?) that allows them to navigate their lives more efficiently.

Furthermore, the subjects favored the study of macroeconomics as they value their power to influence world policies and outcomes. That feeling of intellectual empowerment is common among the interviewed subjects.

So, what is the value of studying macroeconomics? And what do economists do?

Watch: “What is a common myth about economics?” by the American Economic Association, February 2020

Economics is a social science. It is a study on how humans interact when faced with shortage or abundance. It’s a behavioral study at its very core. Macroeconomics, by extension, is a behavioral science of nations as a whole, i.e., what drives nations to open or close their markets, to devalue their currencies, or to raise taxes. One can develop decision-making skills, which was strongly echoed by the aforementioned study.

Students or new learners also develop in-depth analysis, critical thinking, and sound forecasting skills through the study of the field. Yes, forecasting, because there is still a significant debate whether economics and by extension, macroeconomics is a science or not (The Guardian, 2015).

To be clear, Macroeconomics is a social science. As such, models and histories are used to describe macroeconomic phenomena, and statistics are also used to define economic upturn or downturn. The outcomes are quantifiable, but they are, by no means, an indicator of how things will turn out if the same phenomena or scenario happens in the future. This is all because the global economic landscape is ever-changing.

For example, the so-called Great Recession of 2008 is caused by the housing bubble due to high-risk mortgage loans, or “Ninja” loans (IRLE, 2018), where banks lent money to high-risk borrowers. The impending Coronavirus recession (or depression, depending on how long this downturn will last) is caused by the viral pandemic that resulted in nations locking down their boundaries, leading to market and employment stoppage.

Should a recession or depression happen 20 years from now, even the brightest economists would not be able to indicate how would countries or industries react precisely. The economic landscape and the players would undoubtedly be different by then, and also because economics is not an exact science.

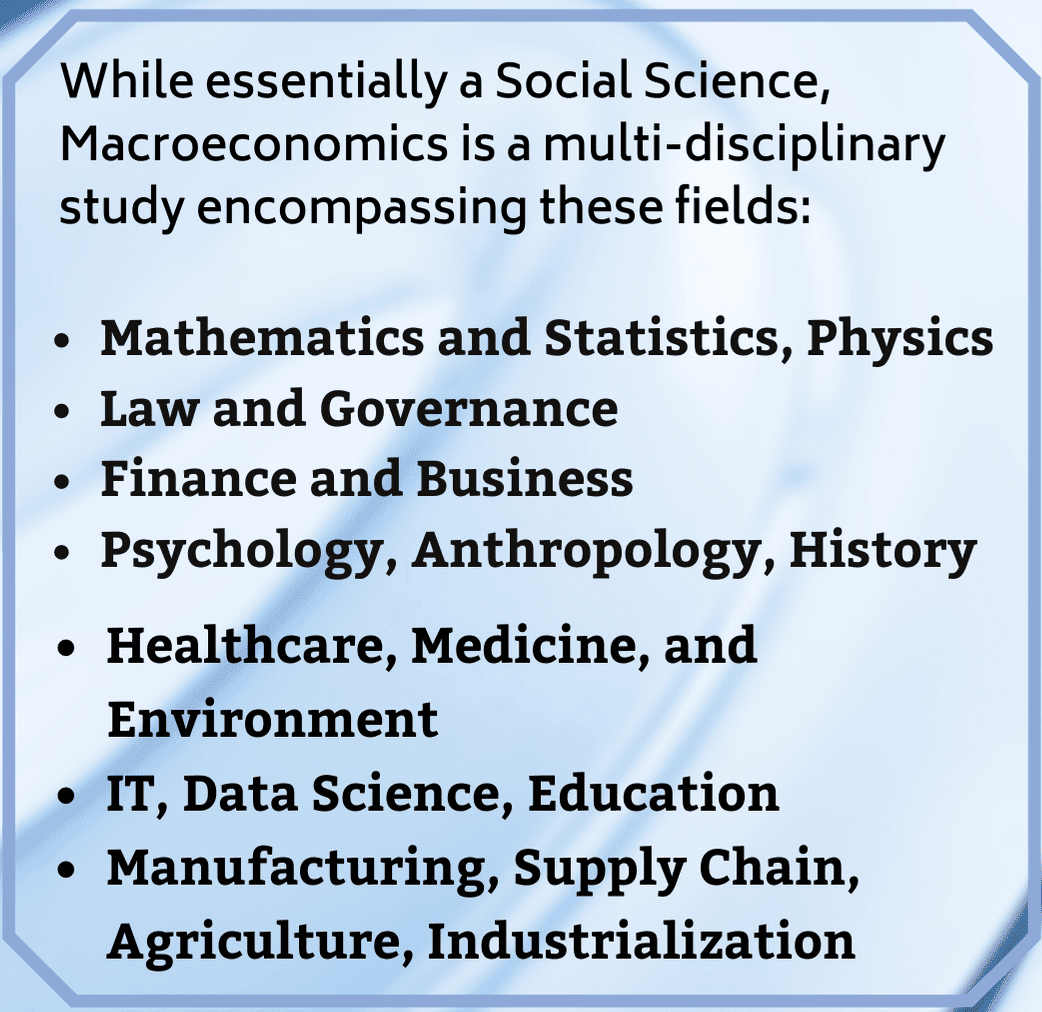

Again, it is a social science. But it is a social science should not be thought of as a limiting factor it intersects various disciplines, like:

- Mathematics and statistics, and even physics

- Law and governance

- Finance and business

- Psychology, anthropology, history

- Healthcare, medicine, and environment

- IT, data science, education

- Manufacturing, supply chain, agriculture, industrialization

And all these make the field a multi-disciplinary study. In the video below, you’d be surprised as to how a medical doctor successfully navigates the healthcare industry or how a Google researcher can insightfully interpret data thanks to their background in economics.

Just like meteorologists and weather forecasters, economists are provided with tools (data, statistics, history, reports) to methodically explain economic occurrences, to provide insight and predict possible outcomes, and make sound forecasts. We should not expect exact answers or explanations.

However, it still instills in us the value of critical thinking, strategy, logic, interpreting relationships. We need to understand better supply and demand. We learn about making use of our resources, whether scarcity or abundance prevails, because economics also teaches us that occurrences are cyclical, just like the seasons or the weather.

All these skillsets gained through the study of macroeconomics can be applied not only for economic analysis but in real-life situations, as well. After all, economics is all around us. Even the smallest decisions, such as driving or commuting to work, are an economical decision.

To quote a line from a 2013 editorial in The Harvard Crimson, “Economics is attempting to neatly model a very messy world…,” which is precisely what it does.

- Macroeconomics is a field of Economics that examines a nation’s economy or the global economy as a whole.

- What’s being reported in the news about a country’s economy or about the global economy’s impending recession, for example, is an example of macroeconomics at play.

- Macroeconomics is a social science that intersects with various other disciplines, whether it’s scientific or mathematical and even the liberal arts.

- Macroeconomics teaches us to be better and more insightful decision-makers. Our everyday decisions are examples of simple economics.

- Macroeconomics is not an exact science but allows us to gain insight into past and current events, and to forecast future events based on past and current information soundly.

- Taking cues from the last video clip (video clip 4), can you think of how other professions can benefit from even the basic knowledge in economics?

- Go through your regular, daily routine, and list down the decisions you think are economical.

COURSE OBJECTIVES

By the end of this course, readers are expected to:

- Gain a novice understanding of what macroeconomics is and how it relates to the concept of economics as a whole

- Distinctly differentiate macroeconomics and microeconomics

- Gain a novice understanding of the aggregated indicators and relate these to real-world economic events or occurrences

- Distinctly differentiate a fiscal policy versus a monetary policy

- Be conversant in the field of macroeconomics, e.g., explain in one’s own words the content of a short finance report by leading news outlets such as CNBC, MSNBC, Bloomberg, etc., or be able to carry a two-minute conversation with a company’s Chief Financial Officer (CFO)

- Be able to construct one or two high-level solutions to today’s macroeconomic woes, i.e., if you are the sitting president of any country grappling the effects of the Coronavirus pandemic and the subsequent economic recession, what would be your first move and why?

BASIC THEORIES, MODELS AND CONCEPTS IN MACROECONOMICS

Origins and Theories of Macroeconomics

Adam Smith as the Father of Economics and Capitalism

Before the Great Depression of 1929, economists only operated under the classical model proposed by Adam Smith. Under his philosophy, the notion that markets would always return to equilibrium because of free-market trade became the guiding light of economies from the period of the industrial revolution until before the Great Depression.

He authored what would be one of the most notable – if not the most notable – books of the 18th century, The Wealth of Nations. One of the key takeaways from his work was the concept of the “Invisible Hand,” which is a combination of the concepts of free-market trade, human nature to promote self-interest or profit motives, and the division of labor leading to mutual trade interdependencies. As a result, society reached its maximum economic potential organically at that time, without the interference of the government.

However, the effects of the First World War were still prevalent in the 1920s, leading to the suspension of the Gold Standard, which was the “gold standard” for currency valuation and exchange rates. Nations like the U.S., U.K., Germany, France, and Japan tried to conserve whatever resources they have left. This then resulted in these nations isolating itself from the world, thus disrupting international trade, something that Smith’s classical model didn’t foresee.

During the Great Depression in 1929, his ideologies didn’t hold up. While economists at the time were aware of the relevance of factors such as inflation, the relationship of unemployment to the law of supply and demand, or the GDP (a nation’s output)—which we now call aggregate indicators or variables—it seemed as though had a limited view on the effect these factors had in the economy.

They held on to the long-accepted idea that the market will always take care of itself and reach a state of balance organically (thus, the term “invisible hand”) as long as people are allowed to trade at will.

John Maynard Keynes: The Father of Modern Macroeconomics

In 1936, John Maynard Keynes released the book “The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money.” As the title implies, Keynes focused on the behavior of the factors that were ignored in the classical approach: the aggregated indicators which are unemployment, production or output, and money.

His ideologies are what gave birth to the subfield of macroeconomics because at the core of his new approach is the vital role of the government in maintaining stable economic growth or interfering with fiscal and monetary policies when a downturn is imminent.

Keynes also added that downturns are inevitable, even recessions, and private entities are expected not to spend given these phenomena. This is where the government comes in. Ever heard the terms “government spending” or “stimulus package”? That is the government doing its part to keep its nation’s economy rolling even if it’s only minimal. In the short-term, after all, any economic movement is better than economic stagnation.

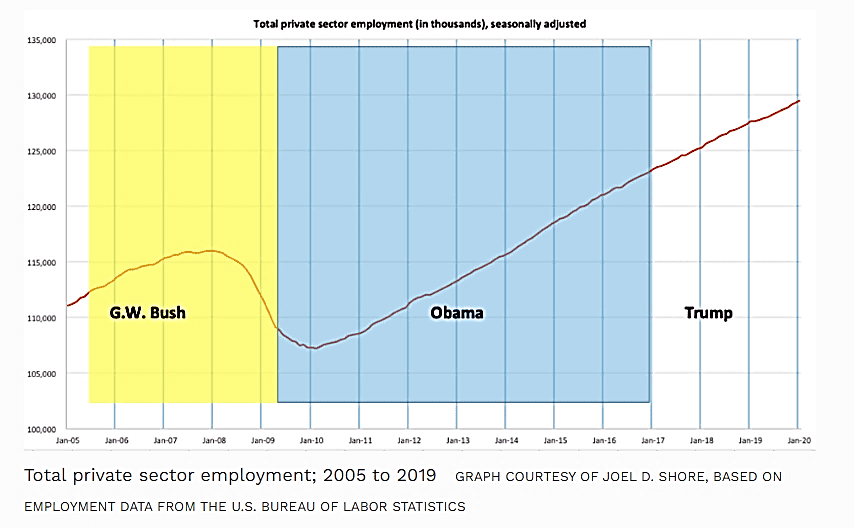

An example of Keynesian Economics put into practice was the response of the Obama Administration to the derailing effects of the 2008 economic recession. The enactment of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 (also known as ARRA or “The Recovery Act”) and the American Jobs Act of 2011 encouraged employers to hire more workers in exchange for a payroll tax holiday.

It also implementing tax cuts and reliefs to families and employees, thus, preventing mortgage defaults and preventing the retrenchment of front-liners like cops and firefighters, among many others.

Infrastructure projects are also a key ingredient in Keynesian Economics, and this has also been adopted by both legislations as a way to regrow the job market and even motivate small businesses to bid for projects.

And in true Keynesian form, the American economic growth from 2009 to 2020 (before the coronavirus pandemic) was slow and steady. A steady rate of employment in the private sector was also reported by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) from halfway of Obama’s first term stretching onto the Trump administration, right before the coronavirus pandemic.

Many economists, advisers, and even politicians are still at odds about which economic model (i.e., classical or Keynesian) should their countries follow, especially in free-speech countries like the U.S. (NPR, 2011). History reveals, however, that a country has better chances of bouncing back after an economic crisis if the government intervenes.

They mind the spending, as well as the implementation of tax cuts and stimulus programs to create jobs and lessen the burden of entrepreneurs, even at the risk of running a deficit, strongly echoing the ideas of the father of modern macroeconomics.

- Long before the 1929 Great Depression, the prevailing economic ideology was the concept of Free Market Trade by Adam Smith, the father of economics.

- Smith was also the proponent of the “Invisible Hand.” According to him, it is the guiding force that allows markets to achieve stability on its own.

- When the 1929 Depression happened, no one could explain why it happened, nor could anyone propose an immediate solution to counter it as it was not covered by Smith’s classical models.

- John Maynard Keynes, the father of modern macroeconomics, was the proponent of the ideology that aggregate variables such as GDP, unemployment, inflation, and interest rates are at play. He published a book about it seven years after the depression.

- Today, governments are adopting Keynesian Economics with a combination of neoclassical models. But several government policies still strongly echo Keynes’ models.

- Do you think a purely Keynesian model of macroeconomics suits today’s economic landscape, which is characterized by an abundance of online companies and the rise of cryptocurrencies?

- How will a Keynesian model of macroeconomics explain the current economic recession brought about by the coronavirus pandemic?

Macroeconomics and Microeconomics: Differences and Dependencies

Macroeconomics and Microeconomics are two of the complementary sub-fields of economics (a third subfield has been recently acknowledged, and this is Econometrics, which is the application of statistics and mathematics in interpreting economic data).

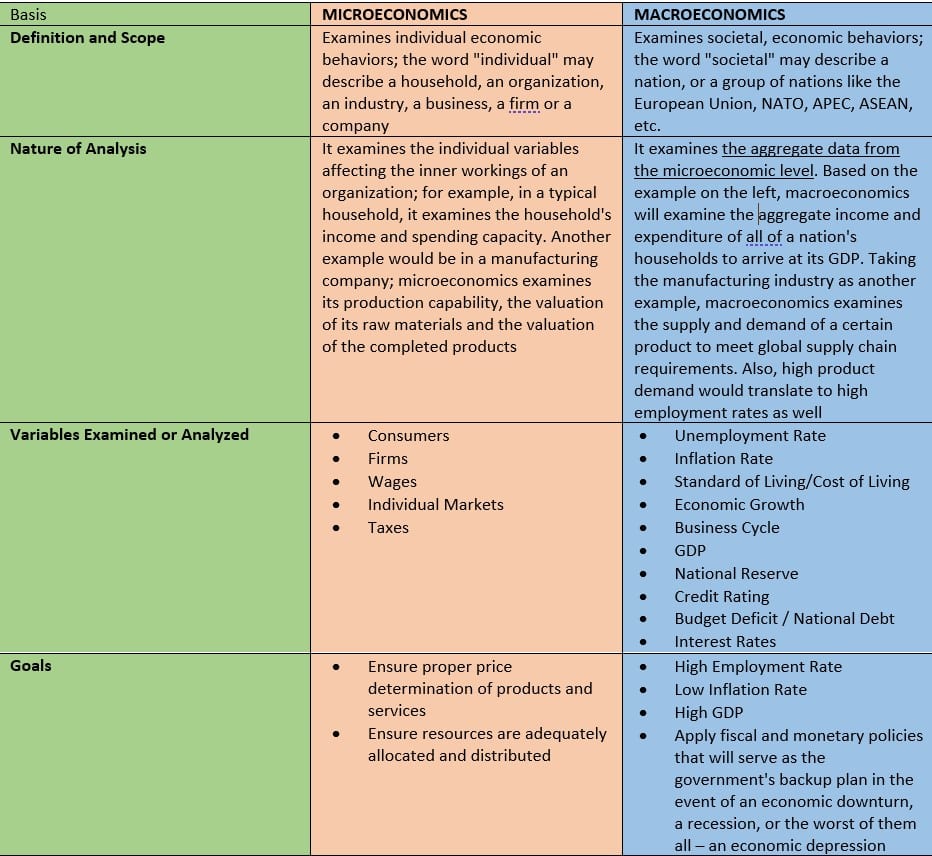

Simply put, one talks about the economy as a whole, which is macroeconomics, and the other – microeconomics – has a more focused area of study and analysis. The table below further describes the distinction and dependencies between the two fields:

- Macroeconomics and Microeconomics are different sides of the economic coin. Though, a third sub-field of economics now exists, called Econometrics.

- Macroeconomics tackles large economies. Meanwhile, microeconomics looks at local economies, individual workers or spenders, individual firms, and similar entities.

- Microeconomics plots the income, output, and expenditure of individual consumers or businesses. The aggregate of these variables representing a nation is what macroeconomics examines.

- Perform a microeconomic assessment of your finances. Compute your net monthly income and expenditures over the last six months and evaluate your financial health.

- Make a monthly appropriation or budget of your income vs. expenses. Do you have enough saved for emergencies? Are your resources or funds properly allocated and distributed?

- Compare your local business news to the reports of the likes of CNBC, MSNBC, or CNN Money. Do you see and hear any difference or distinction between micro and macroeconomics? Use the table above as your guide.

Aggregated Variables of Macroeconomics

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Watch: “What is GDP and Why Should You Even Care?” by the International Monetary Fund, February 24, 2020

GDP is an economic indicator of a country’s production capability (production approach), spending power (expenditure approach), or income (income approach) within its borders for a fiscal year (however, at times, it is reported every quarter). It operates under the logic that all these activities will require money. If a country can carry on these activities, the GDP would indicate a healthy economy, at least in that respect.

There are a few caveats to the GDP, though. One, it does not measure voluntary work. Take note that based on the definition above, there are three approaches to measuring GDP – production or output, expenditure and income – and the one thing these have in common is the exchange of money.

A firm will need money to produce products and, in exchange, will get money by selling those, while both expenditure and income involve the exchange of payment for commodities bought or services rendered, respectively.

Second, GDP, as the term implies, is a “gross” measure of a country’s output. It does not take into account the depreciation of fixed, tangible assets such as real estate, equipment, or other capital stock used during production. If depreciation is to be accounted for, then the resulting data will be the country’s net GDP.

Third, it is crucial to account for inflation or the change in the value of money or currency and an indicator of how expensive commodities are during a specified period. This is so because the GDP is captured using current prices and is used to compare economic health between two periods in time, say two different years or quarters or even periods. Using a price deflator, the real GDP is captured by statistically adjusting the nominal GDP value to account for inflation.

Inflation

Have you ever heard your grandparents or even your parents say how cheap things were back in the day? Then, they would be in awe when they find out how much does the same item cost today. That is the concept of inflation. It measures the monetary value of products over time or what one can buy with the same amount of money before and now.

Simply put, it measures or describes the rise in prices and the devaluation of a country’s currency. If you live in Venezuela, there’s a chance that no matter how many Venezuelan Bolivars you have with you, you won’t be able to buy anything (aside from the fact that there’s nothing to buy in stores anymore).

So, if the inflation in a country is described as high, or in Venezuela’s case, hyperinflated, then there’s an increase in the prices of commodities that affect public expenditure. The exact effect on the purchasing power is determined by the speed at which prices rise and the nature of the disruption of the supply and demand relationship. The following are the two established causes of inflation:

- Demand-Pull Inflation: The heightened increase in demand for a particular product or service drives the prices up if the supply can’t keep up. It could be one of the paradoxes of a rapidly thriving economy and high purchasing power—rapidly increasing expenditures both by the public and the government, plus lax monetary policies like low-interest rates—leading to more money going out and less money going into banks and government reserves.

- Cost-Push Inflation: A timely example would be the price surge by as much as 300 percent for face masks (LA Times, 2020) amidst the coronavirus outbreak. With nations going on lockdown because of the outbreak, raw materials have become scarce, and production of face masks went to a screeching halt. Hospitals and governments are scrambling to procure masks for its front liners and are blindly paying hefty prices just to have stocks ready. It is the cost of making the product that drives the price up.

In Venezuela’s case, the hyperinflation was caused by a combination of socioeconomic and political unrest and ineffective socialist economic policies like stringent price controls on essential commodities. This disabled business owners and producers, which then primarily affected supply. When a different policy was enacted, it crippled the poorest sectors of its economy.

Unemployment

Of all the aggregated markers of macroeconomics, many economists would say that unemployment is the most important and more realistic of all, as it uses human beings and not prices or other intangible factors to measure economic health.

To use the coronavirus recession as an example, millions of people worldwide lost their jobs due to firms shutting down either because of lockdowns or permanently because of bankruptcy. Being jobless is the most apparent and most impactful indicator of a failing economy, whether from an individual perspective, or a national, or even a global perspective.

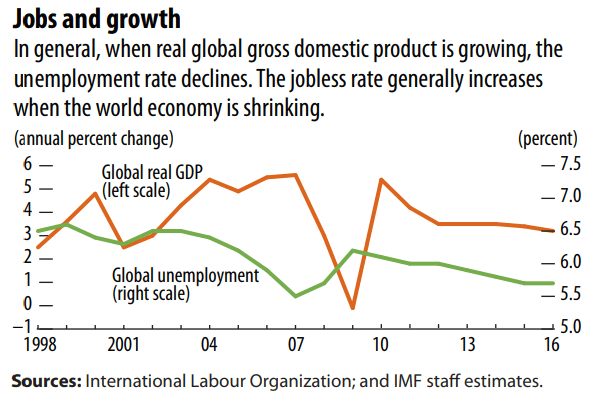

Unemployment is usually measured against the GDP, as the former has an inverse dependency with the latter (Okun’s Law). It is only logical that if a country’s economic activity is on the rise, then the rate of unemployment is – or better yet, “should” – fall, as an increase in production will require more workforce, thereby providing jobs.

However, when the economy recovers after a recession as it did in 2008 and 2009, the rise in GDP would not immediately signal the fall of the unemployment rate. Its decline was observed after the economy has stabilized, months after the recovery period.

This is because during recovery, some businesses, in an attempt to catch up with demand and losses, would employ the same number of employees performing more work than usual. So, an increase in output can be observed but not a decrease in unemployment. This event is called “jobless recoveries.”

Interest Rates

Interest rates are one of the many tools central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve use to stabilize a country’s economy. When a recession is imminent, it lowers the interest rates to stimulate the economy, as negative interest rates will entice loans and expenditures. With a healthy economy, interest rates are high. Thus, consumers and firms are less likely to take out loans. This safeguards the economy in case inflation occurs.

When a country’s central bank depresses interest rates to a negative point, it safeguards the economy against deflation. Deflation is equally harmful to an economy as inflation is. Whereas inflation is either a case of “too much money but nothing to spend on” or “too high a price but got no money to spend on,” deflation is all-around bad news for the economy.

Consumers do not want to spend their money in the anticipation that prices might drop even lower. What a negative interest rate does is it motivates spending by incentivizing it, so in the real world, this would translate to borrowing being more advantageous than saving one’s money in the bank, which is the aim of such a move.

The Bank of Japan (BoJ) was the first country to institute negative interest rates in 1994 to combat deflation. Two decades later, the European Central Bank (ECB) followed suit, and on March 15, 2020, the U.S. Federal Reserve did something similar. It reduced interest rates to almost zero percent (between 0% and 0.25%) in an attempt to cushion the virus’ blow to the economy.

- The primary aggregate variables concerning macroeconomics are GDP, inflation, unemployment, and interest rates.

- GDP, inflation, and unemployment are indicators of economic health. Interest rates, on the other hand, is a tool used by central banks to control cash concentration in the market, preventing inflation or deflation.

- GDP measures the monetary output or productivity of a country. It measures three things: production, income, and expenditures.

- Inflation is used to measure the change in the value of goods and currency over time. Not all inflations are harmful to the economy. A rapid rise in the economy where consumers spend too much and too quickly will cause a high cash concentration in the market that will drive prices upwards. This is an example of harmful inflation. Stable and controlled inflation is necessary to prevent deflation, or the strong reluctance of consumers and businesses to spend money and apply for loans, leading to cash depletion in the market.

- Unemployment is the most impactful macroeconomic aggregate variable since the source of data directly comes from the employees themselves.

- GDP and unemployment have an inverse relationship. Where the GDP is high, the unemployment rate is low (in a fully recovered or stable economy).

- Inflation, deflation, and interest rates are also dependent on each other. When inflation is imminent, interest rates are high to prevent excessive loans and spending. When deflation is imminent, interest rates are low to encourage borrowing and spending.

- Gather data about your country’s GDP, unemployment, inflation, and interest rates from the previous fiscal year. Try to interpret and correlate the findings and evaluate from your perspective if you felt any semblance of economic growth, downturn, or plateau.

Macroeconomic Policy Instruments

What are Macroeconomic Policies?

When the economy is in turmoil, macroeconomic policies are the “playbook” of governments on how to control the damage and prevent the economy from bleeding continuously and profusely. There are two generally well-known and universally adopted macroeconomic policies, the Fiscal Policy and the Monetary Policy.

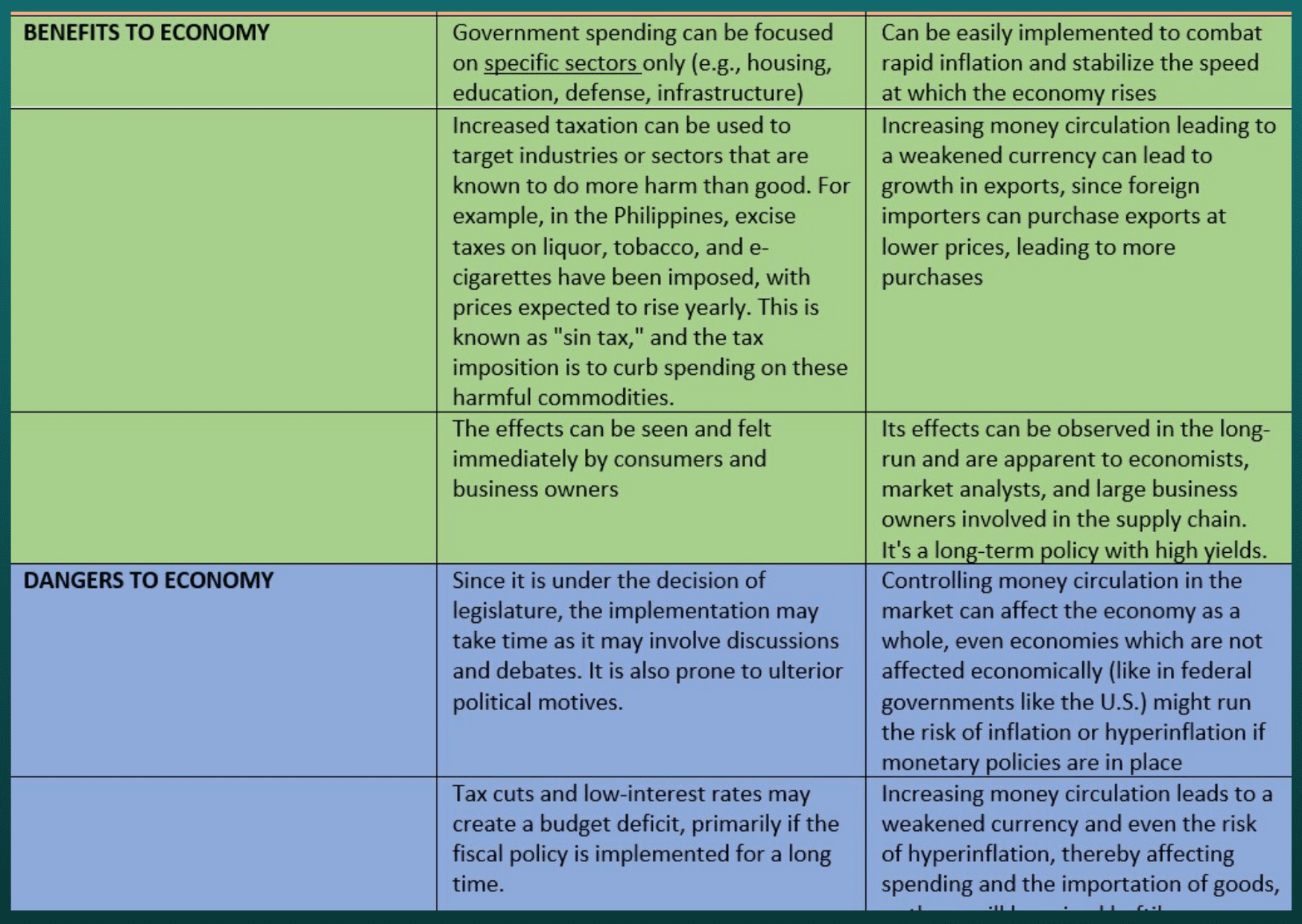

Fiscal Policy and Monetary Policy

Fiscal Policy is backed by legislature, which is why sometimes, it is labeled as politically motivated. It aids an ailing economy by basically picking up the slack for taxpayers through tax cuts or reliefs and covering for the economy by using its reserves to fulfill its socioeconomic financial obligations such as housing, healthcare, or job creation, and this is known as government spending. When the economy has normalized, it will do the opposite – increase taxes and minimize government spending.

On the other hand, the aim of Monetary Policy, as the term suggests, is to curb the money supply or circulation, and this is done mainly by a government’s central bank. If the economy needs a jumpstart, the central bank will pump money into circulation by lowering interest rates, thereby motivating consumers and businesses to take out cheaper loans and to spend more.

An example would be the previously mentioned implementation of the U.S. Federal Reserve of near-zero interest rates to entice money lending and spending, thereby increasing the circulation of money amidst the coronavirus pandemic.

The opposite is also a pillar of monetary policy whereby stringent loan measures like increased interest rates are being implemented to discourage lending and thereby control excessive money in circulation.

Economists would say that these two policies work best when implemented together; after all, each policy has a different set of parties to be accountable for – the legislature for fiscal policies and the non-partisan central bank for monetary policies.

More importantly, if both are effectively and simultaneously implemented, the government must take advantage of the low borrowing interest rates courtesy of the central bank. Doing this enables them to continue to fund infrastructure projects, healthcare, education, defense system, and other sectors that rely on government funding.

That’s fiscal and monetary policies working hand-in-hand to raise a slumping economy. But how come this isn’t happening, you may ask? It’s simple – politics.

- The primary macroeconomic policies governments use fiscal policy and monetary policy.

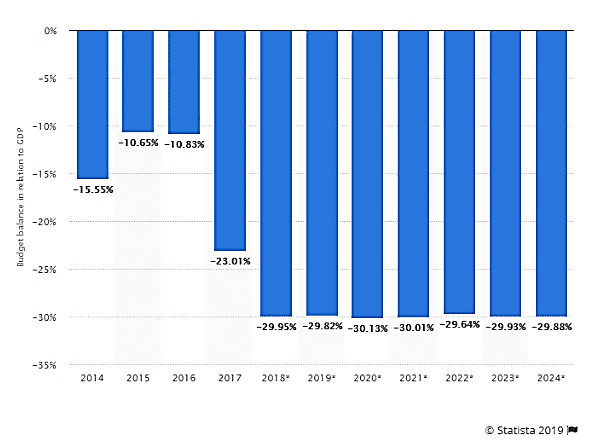

- Fiscal policy centers on government spending and tax cuts to ease the burden of employers, employees, and business owners. Legislators call the shots on this one. A caveat to this policy, primarily if implemented over a long period, is that it might balloon a government’s budget deficit.

- A monetary policy centers on lowering or raising interest rates, depending on what the economy needs, whether inflation or deflation is imminent. The central bank is responsible for implementing the policy and controlling interest rates.

- Monetary policy is usually helpful in addressing the issue of rapid inflation. However, care must be exercised in instituting this policy since its effect on the economy is more generalized than fiscal policy. Areas or sectors which are not affected might manifest a reverse impact, such as inflation or hyperinflation.

- Chances of recovery are greater if these policies are enacted together as these are complementary, and the strength of each policy can be used simultaneously to strengthen a weakened economy. However, in most governments, politics get in the way.

- Cite country examples where a simultaneous enactment of fiscal and monetary policies was observed. Was it successful or not? Describe the outcome using the macroeconomic aggregated variables.

- How does politics get in the way of effective economic planning and implementation?

- With the coronavirus outbreak sending the global economy into uncertainty, devise one or two ways through which your country’s economy can stimulate its economy using the basics of fiscal and monetary policies. Gather data from the previous fiscal year, and don’t forget to describe your plans in terms of the macroeconomic aggregated variables – GDP, inflation, unemployment, and interest rates.

References

- Taylor, Timothy; Greenlaw, Steven A. (2016). Principles of Economics. Openstax by Rice University.

- The University of Illinois, Department of Economics: What is Economics https://economics.illinois.edu/academics/undergraduate-program/what-economics

- Business News Daily: What is Economics? https://www.businessnewsdaily.com/2639-economics.html

- Rethinking Economics Netherlands: What is Economics? https://www.economicseducation.org/what-is-economics

- American Economic Association: What is Economics? https://www.aeaweb.org/resources/students/what-is-economics

- Gitman, Lawrence J.; McDaniel, Carl; Shah, Amit; et al. (2008). Introduction to Business. Openstax by Rice University

- Marotta, David John (2020). Longest Economic Expansion in United States History. Forbes Magazine Online.

- Hirst, Tomas (2015). A Brief History of China’s Economic Growth. World Economic Forum.

- Saefong, Myra P. (2016). Oil is on the Verge of Equilibrium as Output Declines Slow. MarketWatch.

- Egan, Matt (2014). 2008: Worse than the Great Depression? CNN Money.

- Bond, Casey (2020). Recession vs. Depression: What’s the Difference and Which One Are We Headed Toward? Huffington Post.

- The Federal Reserve FAQs (2017). Video: What is Macroeconomics? The U.S. Federal Reserve.

- CNBC (2020). Video: Why the Coronavirus Recession is Unlike Any Other? CNBC YouTube Channel.

- Mearman, Andrew; Papa, Aspasia; Webber, Don J. (2009): Why Do Students Study Economics?” University of the West England, Bristol.

- Luyendijk, Joris (2015). Don’t Let the Nobel Prize Fool You. Economics is Not a Science. The Guardian.

- Coghlan, Erin; McCorkell, Lisa; Hinkley, Sara (2018). What Really Caused the Great Recession? Institute for Research on Labor and Employment (IRLE), University of California – Berkeley.

- Chladek, Natalie (2017). 5 Reasons Why You Should Study Economics. Harvard Business Review Online.

- American Economic Association (2020). Video: What is a common myth about economics? https://vimeo.com/389776283

- American Economic Association (2015). Video: A Career in Economics… It’s Much More Than You Think. https://vimeo.com/135871291

- Blenman, Joy (2020). Adam Smith and the Wealth of Nations. Investopedia.

- Office of the Historian, U.S. Department of State: The Great Depression and U.S. Foreign Policy https://history.state.gov/milestones/1921-1936/great-depression

- Rodrigo, G. Chris (2020); Micro and Macro: The Great Divide. International Monetary Fund.

- Office of the Press Secretary, The White House (2011). Fact Sheet and Overview: American Jobs Act. President Obama’s White House Archives.

- Jahan, Sarwat; Mahmud, Ahmed Saber; Papageorgiou, Chris (2014). What is Keynesian Economics? International Monetary Fund

- United States Congress: 111th Congress (2009). H.R.1 – American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009. United States Congress.

- Jones, Chuck (2020). Obama’s 2009 Recovery Act Kicked Off Over 10 Years of Economic Growth. Forbes Magazine Online.

- Welna, David (2011). Keynes’ Consuming Ideas on Economic Intervention. National Public Radio.

- Sanchez, Valentina (2019). Venezuela Hyperinflation Hits 10 Million Percent. ‘Shock therapy’ May Be (the) Only Chance to Undo the Economic Damage. CNBC Online.

- D’Angelo, Matt (2020). What is Inflation? Business News Daily.

- Gutierrez, Melody; Elmahrek, Adam (2020). Suppliers Cash In (sic) as California Taxpayers Hit with Wildly Inflated Prices for Masks. Los Angeles Times.

- BBC News (2020). Venezuela Crisis: How the Political Situation Escalated. BBC News Online.

- Hasan, Mehdi (2012). Unemployment Matters More than GDP or Inflation. The Guardian.

- Oner, Ceyda. Unemployment: The Curse of Joblessness. International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/fandd/basics/pdf/oner_unemploy.pdf

- Business Insider (2020). Video: What 0% Interest Rate Really Means. Business Insider YouTube Channel.

- Goldman, David (2020). Federal Reserve Cuts Rates to Zero to Support the Economy During the Coronavirus Pandemic. CNN Business.

- Smith, Kelly Anne (2020). Negative Interest Rates Explained: How Could They Affect You? Forbes Magazine Online.

- Luz Lopez, Melissa (2020). Duterte Signs Law Raising Taxes on Alcohol, E-cigarettes. CNN Philippines.

- Bernstein, Jared (2015). Monetary and Fiscal Policy Should Comprise a One-two punch. But That’s Not Happening. Washington Post.

- The Atlantic (2013). Video: “Monetary Policy: A Quick and Dirty Explainer.” The Atlantic YouTube Channel.

Get a PDF copy of this Crash Course in Macroeconomics by Online-Bachelor-Degrees.com